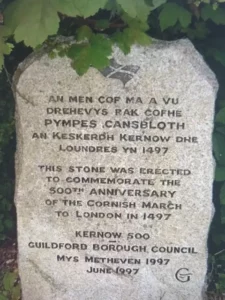

In a grassy corner at the top of The Mount overlooking Guildford is a memorial stone. It is called the “Kernow Stone” – but why is it there and what is the background to its name?

The story begins in 1496. After disagreements regarding new regulations for the tin-mining industry, King Henry VII suspended the operation and privileges of the Cornish stannaries, a major part of the county’s economy. These privileges, which included exemption from certain royal and local taxes, had been granted under a deal with Edward I in 1305. With Scotland threatening to invade England the King levied an extraordinary series of financial demands on his subjects, a burden which fell more heavily on Cornwall than most areas.

The people of Cornwall were incited into armed revolt with the supposed aim of removing the two servants of the king considered responsible for his taxation policies, Cardinal John Morton and Sir Reginald Bray.

An army some 15,000 strong marched towards Devon, attracting support in the form of provisions and recruits as they went. In Devon support for the rebellion was far lower than in Cornwall. Entering Somerset, however, they were joined by James Touchet, the seventh Baron Audley who as a member of the nobility with military experience was gladly received and acclaimed as their leader. The rebels continued towards London, marching via Salisbury and Winchester.

When the King learned of the close approach of the West Country rebels to London, and of their strength, he diverted his main army of 8,000 men under Lord Daubeny to meet them. Daubeny’s army camped on Hounslow Heath on 13 June and the next day a detachment of 500 of his spearmen clashed with the rebels near Guildford. Until then, the rebel army had met virtually no armed opposition, but neither had they gained significant numbers of new recruits since passing through Somerset.

Instead of approaching London directly they skirted to the south believing they would gain popular support from Kent. Leaving Guildford they moved via Banstead to Blackheath, an area of high ground south-east of London, which they reached on 16 June. No Kentish uprising materialised. Indeed, forces of Kentish men had been mobilised against them under loyalist nobles. The King had now mustered a large army in London so the outlook for the rebels was grim. There was much dismay and disunity among the rebels on Blackheath and thousands of desertions from the insurgency that night.

The Battle of Deptford Bridge (also known as Battle of Blackheath) took place on 17 June 1497. The King’s forces were deployed to surround the Blackheath high ground where the rebel army had camped and where its greater part was still positioned. Lord Daubeny attacked along the main road from London, crossing Deptford Bridge and taking it from the rebels. He then led the attack up into the rebels’ main position on the heath. So bold was his leadership that he became separated, surrounded by the enemy, and temporarily captured. The rebels could have killed him, but actually let him go unhurt. Overwhelmingly outnumbered, surrounded, poorly trained and equipped and lacking cavalry, their fight was now hopeless. They were routed. Their leaders were captured and subsequently executed.

In 1997, a commemorative march named Keskerdh Kernow (Cornish: “Cornwall marches on”) retraced the original route of the rebels from St. Keverne to Blackheath to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Cornish Rebellion. A statue depicting the Cornish leaders was unveiled at St. Keverne and commemorative plaques were unveiled at Guildford and on Blackheath.

In 1997, a commemorative march named Keskerdh Kernow (Cornish: “Cornwall marches on”) retraced the original route of the rebels from St. Keverne to Blackheath to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Cornish Rebellion. A statue depicting the Cornish leaders was unveiled at St. Keverne and commemorative plaques were unveiled at Guildford and on Blackheath.

A visit to this memorial is included in a Guildford Walkfest event being hosted by Surrey Hills Society on Friday 16th September. Details are on the SHS website “Events” page and on the Walkfest website www.guildfordwalkfest.co.uk Why not join us to see the stone for yourself?

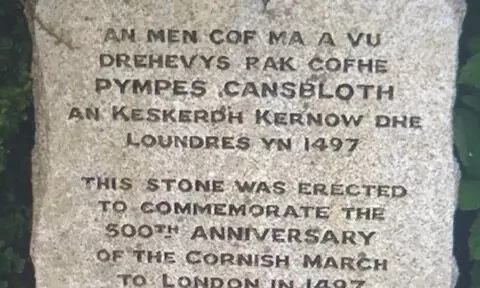

Surrey Hills Society members were recently treated to a fascinating talk on Ada Lovelace by local historian, Roger Price. This was followed by a tour of the garden before returning for lunch on the terrace. After lunch we were able to access the exquisitely decorated family chapel.

Surrey Hills Society members were recently treated to a fascinating talk on Ada Lovelace by local historian, Roger Price. This was followed by a tour of the garden before returning for lunch on the terrace. After lunch we were able to access the exquisitely decorated family chapel.

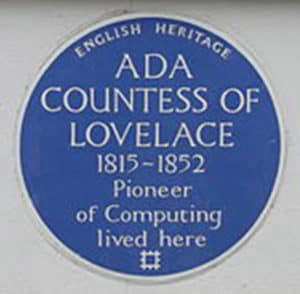

The UK quarrying industry is one of the oldest industries in the country and for hundreds of years was an integral part of our industrial heritage. Several formerly active quarries in Surrey have now been transformed into conservation areas and recreational facilities.

The UK quarrying industry is one of the oldest industries in the country and for hundreds of years was an integral part of our industrial heritage. Several formerly active quarries in Surrey have now been transformed into conservation areas and recreational facilities.

The “Folkestone beds” along the foot of the North Downs contain some of the purest silica sand deposits in the country. Its low metal content makes it useful in a range of industries including glass and foundry casting. At its peak Buckland Sand & Silica Co. Ltd, owned by the Sanders family since 1925, had up to 15% of the national sand market. The sand had interesting uses from casting the propellers of the Queen Mary through to the moonscapes on the set of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 A Space Odyssey.

The “Folkestone beds” along the foot of the North Downs contain some of the purest silica sand deposits in the country. Its low metal content makes it useful in a range of industries including glass and foundry casting. At its peak Buckland Sand & Silica Co. Ltd, owned by the Sanders family since 1925, had up to 15% of the national sand market. The sand had interesting uses from casting the propellers of the Queen Mary through to the moonscapes on the set of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 A Space Odyssey. There are plenty of ongoing challenges. “Higher footfall means a better return on the large investment, but overcrowding would spoil the ambience,” said Dominic. Do they think they have succeeded? “Overall, we are very pleased with the results. Although we have had far more visitors than we expected we believe we have been successful in not overcrowding the site. However, we are trying to remain honest about how much lies ahead and what we must do to achieve the standards to which we aspire for our visitors.” And what about Tapwood on the other side of the A25? According to Dominic it is unlikely it will ever be suitable for general public enjoyment due to its topography and location.

There are plenty of ongoing challenges. “Higher footfall means a better return on the large investment, but overcrowding would spoil the ambience,” said Dominic. Do they think they have succeeded? “Overall, we are very pleased with the results. Although we have had far more visitors than we expected we believe we have been successful in not overcrowding the site. However, we are trying to remain honest about how much lies ahead and what we must do to achieve the standards to which we aspire for our visitors.” And what about Tapwood on the other side of the A25? According to Dominic it is unlikely it will ever be suitable for general public enjoyment due to its topography and location.

Perhaps one of the most well-known is Adam Aaronson considered one of the UK’s leading glass artists. At his studio in West Horsley, he specialises in free-blown glass, runs beginners’ courses in glassblowing and designs and makes a range of interior design accessories. Visitors to the studio are welcome Tuesday through Sunday.

Perhaps one of the most well-known is Adam Aaronson considered one of the UK’s leading glass artists. At his studio in West Horsley, he specialises in free-blown glass, runs beginners’ courses in glassblowing and designs and makes a range of interior design accessories. Visitors to the studio are welcome Tuesday through Sunday.

Rowan Duckworth of the Small Robot Company explains how companies like theirs are using AI to help farmers make more informed and precise decision

Rowan Duckworth of the Small Robot Company explains how companies like theirs are using AI to help farmers make more informed and precise decision